Venezuela after Chávez: who stands a chance in the 2013 presidential elections?

Published in Huffington Post.

The death of Hugo Chávez leaves the future of Venezuela in the balance. With elections set for early April, the question of who will replace him takes on new urgency. Here we survey the runners and riders, from the obvious choices within Chávez’s PSUV and the opposition MUD to outliers on both sides.

The Loyalists

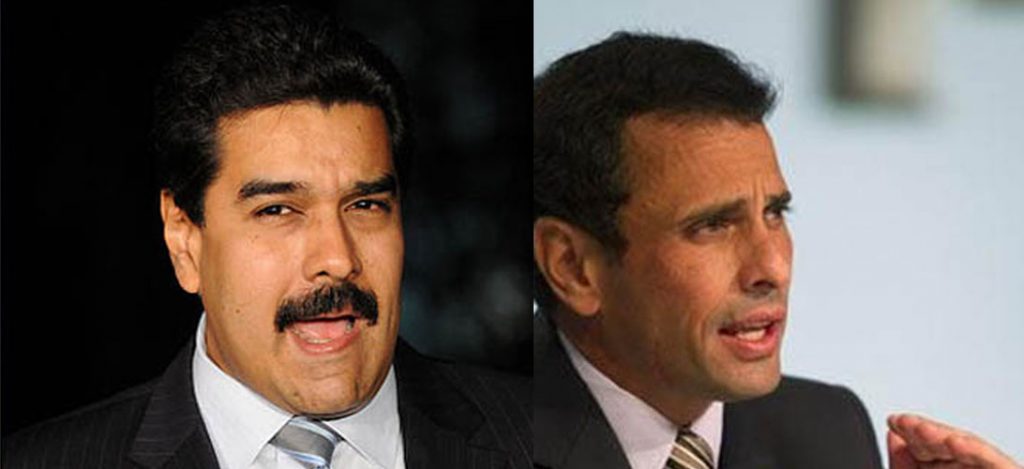

Nicolás Maduro

The frontrunner is Vice-President Nicolás Maduro, one of the few Chavista top brass with a profile high enough to launch a serious bid and the only one to receive “firm, absolute, total, and irrevocable” support in Chávez’s deathbed dedazo (hand-picking for succession).

Maduro’s bond with Chávez is unshakeable, dating back to Chávez’s jailing for a 1992 coup attempt, and their mutual affection could prove crucial in such emotionally charged elections. Having risen through union politics from lowly bus driver to Foreign Affairs Minister, his backstory also offers the same mix of humility and achievement that made Chávez so irresistible to Venezuela’s long-suffering poor. While he lacks the Amerindian features that marked Chávez out as one “from below”, he has neither the phenotype nor the affectations of faux-Western elites at the other end of Venezuela’s pathologically polarized politics.

But the similarities end there. Before taking over Chávez’s duties, Maduro was the quiet man of Chavismo, happily going about his business in the relative tranquility of the diplomatic corps. Thrust centre-stage, he has struggled to fill Chávez’s unfillable boots. Like Gordon Brown grimacing on Youtube, Maduro has aped the style of a world-beating predecessor, and the results have been unconvincing.

Chávez effortlessly juggled pop culture, political theory, folklore, and geopolitics, taking the sting out of “here comes the science!” parts with wit and streetwisdom. Maduro’s bricolage of revolutionary buzzwords can sound like the director’s cut, with all the extraneous scenes left in. Where Chávez stirred the loins even of his critics, even staunch Chavistas applaud Maduro with a hint of politeness.

His once peaceable demeanour might have attracted ni ni floating voters (neither Chávez nor opposition), and simply not being Chávez will still be enough for some. But a poor impersonation of his predecessor could alienate ni nis while leaving Chavistas uninspired.

But Maduro remains the favourite. He has few enemies and is part of a political supercouplea la Balls-Cooper (with attorney general Cilia Flores). And his party recently followed up Chávez’s 11 percentage-point win by taking 20 of 23 state governorships.

He is already wearing the trademark Venezuelan tracksuit, and it will take something special to wrest it from him.

Diosdado Cabello

Another PSUV big hitter is Diosdado Cabello. Though his name amusingly translates as “God-given Hair”, he is a darker character than Nicolás Maduro (“Nick Mature”, fittingly).

Again, his relationship with Chávez is key. He participated in Chávez’s 1992 coup attempt before rising through the ranks of party politics. When Chávez suffered a coup of his own, Cabello stood in for him during the popular uprising until his reinstatement. As Maduro puts it, they are almost father and son.

He enjoys close links with the military, which under Chávez went from being state bully to executor of social programmes and infrastructure projects. As Vice President and Interior Minister amongst many other portfolios, he has gained a reputation as a political junkyard dog, willing to fight for scraps against a belligerent opposition.

But if there is not exactly “something of the night about him”, there is certainly something of the early evening. He stands accused of the kind of coffer-emptying corruption abhorred by Chavistas and opposition alike, and his manner, as one Chavista commentator noted, “can provoke admiration, respect, and loyalty, but also rejection and even fear”.

If the PSUV backed him, it seems unlikely that the country would follow suit.

The Opposition Golden Boy

Henrique Capriles Radonski

Capriles Radonski’s weakness is that he is playing for the losing side. The fractious and fractured opposition has repeatedly failed to defeat Chávez’s PSUV, and without a major rethink it will fail again in 2013.

For all its rhetoric of “centre-left” politics and “social democracy”, the opposition MUD represents much the same constituency whose excesses enabled Chávez’s rise. Granted, incredulous exclamations of “how could this happen?!” have morphed into strategic considerations of “how can we look more like what’s happened?” and in-fighting has been reined in. But in a country as socially and geographically divided as it is politically, they remain ignorant of the suffering of those that – when not busy cleaning the houses of the wealthy – are off voting PSUV.

Despite studies overseas and family connections to a media empire, Capriles Radonski himself has successfully pushed an Average José image. But behind the “new Lula” schtick, his lack of substance could be discovered by an electorate that is no longer the dupe it once was.

The Dark Horses

Henri Falcón

Little known outside of Venezuela but well-liked within it, Falcón would be a wise choice for an opposition that fancied winning.

An important member of Chávez’s early political movements, Falcón is well-acquainted with the Venezuelan left. Yet, after distancing himself from Chávez in his campaign for the governorship of Lara state in 2008, he crossed the floor (diagonally) by joining the moderate-left PPT.

Criticisms of hyper-centralisation chimed with public unease about basic services, corruption, and top-downism (despite much fanfare about participatory democracy). But attacks have been measured in a context that tends to full-frontal warfare, with Falcón pitching to those fatigued by relentless bloodletting.

Where Maduro can be leaden, Cabello menacing, and Capriles Radonski lightweight, Falcón interweaves reason with blood and thunder. He is no Chávez – no one comes close – but he has some of that uniquely Venezuelan appeal and charisma.

Unfortunately, coalition machinations are unlikely to see Capriles Radonski replaced, let alone by someone with frightening, radical-leftist skeletons in his closet.

Francisco Arias Cárdenas

Another outside shot is Francisco Arias Cárdenas, PSUV governor of the oil-rich state of Zulia.

Like Cabello he took part in Chávez’s 1992 coup – his part succeeded whereas Chávez’s failed – and he retains ties to the military. Like Falcón he was involved in Chávez’s rise but defected over creeping authoritarianism.

This fact and other qualities could attract floating voters or habitual anti-Chavistas. As befits his training for the priesthood and ambassadorship to the UN, he can be statesmanlike, but he can also rouse a rabble into voting. Winning the governorship of his home state, an opposition stronghold, suggests an appeal surpassing the limits of either leading coalition. Running against Chávez after their split in 2000, he took nearly 40% of the vote, even with Chávez’s star in the ascendant.

If the PSUV splits between Maduro and Cabello, Arias Cárdenas might represent a viable compromise.

The Winner

Barring any meteor strikes, the tricolore tracksuit should stay with Maduro. Neither Cabello nor Arias Cárdenas shows any sign of mounting an internal challenge. Capriles Radonski has the face recognition and political amorphism that the fragmented opposition can “unite” behind, and they won’t give that up for a risky pinko like Falcón.

The real winner, however, is Chávez, for if there is a common theme here it is the need to demonstrate proximity to him, be it in word or deed. The Bolivarian Revolution was always a transformative project, and if these elections are anything to go by, it may already have succeeded.