Death is the ultimate intimacy: media wrong to show video of Charlie Hebdo policeman Ahmed Merabet’s murder

Ahmed Merabet’s death is not the first I’ve witnessed on screen, but it has troubled me in ways that other deaths have not. Warnings of “distressing scenes” have it backwards. This is not about us as viewers. It’s about him as a human being.

I didn’t choose to witness Ahmed Merabet’s murder. It was shown to me. When I checked the rolling coverage of events in Paris, the headline item was a video of the “apparent killing” of a police officer, warning of “distressing scenes” while reassuring that footage had been edited.

I took this to mean – as it usually does – that it might contain gore or suffering, neither of which I would necessarily choose to avoid. Not only because I’m well aware of their existence, but also because on one level I believe people need to be faced with brutal realities in order to make informed decisions about condemning or condoning them.

What it actually contained was far worse: the last seconds of a man’s life. The moment of his being shot to the ground, his blurred body writhing on the pavement, the raising of his hands in vain hope of survival. The audio added cries of pain and even his last words, clearly audible and – worse still – immediately comprehensible to me as a French speaker. Though I’ve seen it reported backwards, it is the murderer who asks “you trying to kill us?”, to which Merabet replies “no, it’s OK, boss”, before the video blacks out to avoid showing his execution.

Dignity in Dying

So what’s the problem? The viewer has not been exposed to any graphic images and the moment of death itself has not been shown. This misses the point.

The issue here is one of dignity, which is more about Merabet than about us as viewers. Dignity derives in part from autonomy, the ability to choose one’s own path and not be subjected to another’s will. Though the moment of death is not shown, the circumstances very much are, and they show a man diminished, forced into a placatory tone and posture that we as viewers already know to be futile. Even without the moment of death, the video widely available shows us Merabet’s subjection. As one of his colleagues put it, “he was slaughtered like a dog”, but it is our gaze that creates this interpretation.

Those media that blurred his features did at least obscure his individuality and identity so as to neutralise his humanity before it was literally neutralised by his attackers. But this attempt to safeguard his dignity was no match for rolling news, and within minutes stills showing his face were circulating. My brain couldn’t help but map the missing features on to the blurred outline from the video.

But my problem with being exposed to this is not my possible distress. I never knew Ahmed Merabet, but I care about him nonetheless. Since I cannot imagine that he – a policeman no less, the embodiment of state power – would have wanted to be depicted in this way, I don’t want to be forced to play any part in that depiction, even as its passive recipient.

Choosing to Die

Consider the difference with another public death, that of Peter Smedley in Terry Pratchett’s controversial documentary on euthanasia Choosing to Die (2012). There we see Peter, aged 71 and suffering from motor neurone disease, swallowing poison and awaiting death with his wife by his side. This is the most powerful scene I’ve ever seen on a screen, but for its beauty not its horror.

Rather than being diminished by a lack of control, Peter is ennobled by the defiance of nature’s arbitrary cruelty that is inherent in his choice to die in circumstances of his own choosing. Not only that, he has allowed it to be filmed and screened so that others might learn from it. Ahmed did not choose to die, nor in those circumstances, and he had no knowledge that his death would be public.

The Anti-Social Role of Social Media

So who chose to make Merabet’s death public? And who should choose?

In the era of social media, the traditional filters of time and experience are severely weakened. In the case of time, insatiable demand for new news creates a constant rush to publish and shortens the timeframe for editorial judgements. In the case of experience, journalistic ethics built up over centuries are easily bypassed by smartphone cameras and Twitter clicks.

I know from personal experience that things happen in social media which shouldn’t, but once they become news there, they become newsworthy to traditional media. Someone films a murder, uploads it in the heat of the moment, tweets about it; one news site hesitates but runs it; other news sites don’t want to miss the scoop and are now absolved of responsibility for being first to break it; suddenly it’s everywhere.

But regardless of how quickly the media move, the touchstone for journalistic ethics remains public interest. Admittedly, there is something to gain from our witnessing Ahmed Merabet’s death: we see with our own eyes the killers’ mercilessness, even towards someone sharing their North African origins and following the religion in whose name they claimed to act (presuming the suspects have been correctly identified). But this was just one of a set of twelve murders which would have provoked outrage and disgust anyway, so this minor added-value has to be weighed against the cost to Merabet and his family.

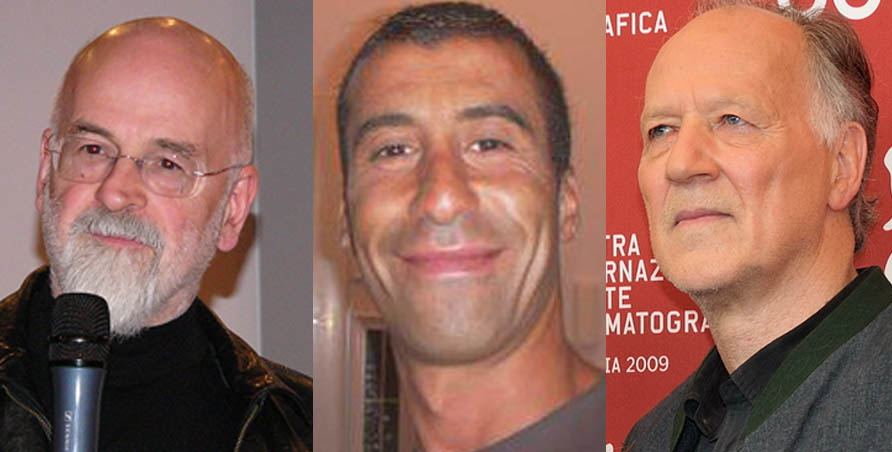

Learning from Grizzly Deaths

A third widely known death, whose intimate reality remains private, shows that there is an alternative.

In 2003 conservationist Timothy Treadwell and his girlfriend Amie Huguenard were killed and eaten by a grizzly bear, with audio of the attack accidentally recorded on their video camera. While making a documentary about Treadwell (Grizzly Man, 2005), director Werner Herzog was faced with the question of how to deal with this material when a close friend of Treadwell’s allowed him to listen to it.

Against the weight of curiosity from both the friend and the viewer, a clearly shaken Herzog not only declines to satisfy the audience, he even exhorts Treadwell’s friend to destroy the tape so that neither she nor anyone else will ever hear it. In a later interview he explained, “you would violate the death and dignity of the two individuals; you just don’t do it!”

Both to avoid the grimmest possibility of all, that his family could like me have seen the edited, blurred video without realising what they were watching, and to avoid violating his own death and dignity, the media should not have shown the video of Ahmed Merabet’s murder.

Intersubjective social goods like dignity are no less important for their intangibility – try defining love or living without it and you’ll see what I mean. In death as in life we must do what we can to protect them.

Image attributions:

1) Ahmed Merabet, profile image, used elsewhere on Huffington Post.

2) “Grizzly Man” (movie poster publicly available via Wikipedia).