I tried not to vote for Corbyn, but I just couldn’t stop myself!

Originally published in The Huffington Post.

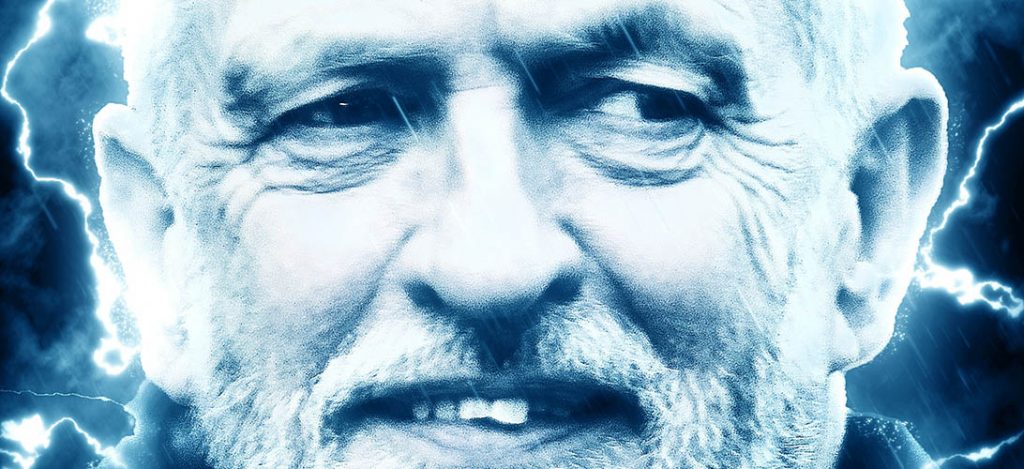

In the face of dire warnings about his economic policies, his electability, and his past indiscretions, I just voted for Jeremy Corbyn in the Labour leadership election. This is why.

“But he’ll destroy the economy!”

The battle over “Corbynomics” has seen letters flying in all directions, with one group of economists arguing that “opposition to austerity is actually mainstream economics” while another claims the exact opposite. This is not entirely surprising, as it only reflects a wider battle over what will become the new “mainstream” after the last one cheerled the global economy over a cliff.

Though this latest mainstream disaster should have dispelled the implication that “mainstream = right”, it clearly hasn’t. And beyond individual Corbyn policies, it’s his challenge to this idea that constitutes the main value of his irresistible rise.

Following Labour’s election defeat, what passed for economic-policy debate was how much ground Labour should cede to the Tory charge that public spending caused the financial crisis. Burnham and Kendall lost my vote here. For a party of the left to demonise public spending is political suicide, and here it would only compound Labour’s unforgivable failure to capture public anger towards the real culprits in the financial sector.

But beyond party-political gains, this is a moral issue: Cameron and Osborne might be content to peddle the lie that “the economy is like a household“, but everyone knowsthe deficit was caused by a public bailout of private losses, and to pretend otherwise is plain wrong.

Getting alternative ideas like People’s Quantitative Easing, a national investment bank, and renationalisation back on the public agenda is a necessary first step in escaping the debt-driven model that caused this mess in the first place. To quote two of my former professors Colin Hay and Tony Payne, directors of the Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute:

“What Labour needs most fundamentally is to find, fashion, forge, beg, borrow or steal a narrative about the economy that is capable both of challenging the terms of the old debate and setting the framework of the new”.

It’s a mammoth task but also a crucial one that will have consequences for us all. Only Corbyn is willing to go anywhere near it.

“But he’ll make the Labour party unelectable!”

Just as they cannot see beyond an economic framework inherited from New Labour, Burnham, Cooper, and

Just as they cannot see beyond an economic framework inherited from New Labour, Burnham, Cooper, and

Kendall’s political calculus is skewed by their apprenticeship under Blairism. And just as it’s hard to believe that mainstream economists now understand a system they disastrously didn’t in 2008, it’s hard to give credence to the trio’s claims to know how to win an election.

Did they get it right on the Scottish referendum? In the general election? Or in 2010 for that matter? Did they feel the discontent fuelling Corbynmania and anticipate the threat he represented? No, in all cases. “But Tony won in 1997!” ignores not only that his stock has been falling ever since, but also that the financial crisis has created a different political landscape.

Even in 1997 Blair’s politics were not inevitable, and I am surely not alone in wishing his predecessor John Smith had been able to contest an election he would “undoubtedly” have won if not for his untimely death. Others draw comparisons with Michael Foot and Tony Benn, but the relative moderniser Smith is the leader Corbynmost admires.

From this political space he could pick up both nationalist defectors returning from the SNP and leftist defectors returning from the Greens and Lib Dems. He could also address at least the economic concerns of UKIP voters essentially wished out of existence by major parties at the last election, not to mention his apparent appeal amongst “the disillusioned who didn’t vote“. His sincerity, meanwhile, provides a breath of fresh air across the board, and though its precise political value is hard to judge, 81 per cent of participating viewers of the final televised debate deemed Corbyn the “winner”.

Granted, he is not Obama, and I sympathise with those who share Corbyn’s politics but fear the wider electorate will not. But the lagged-Conservatism approach has already failed twice, and Frankie Boyle’s “office manager back from a course” (Kendall), “Fireman Sam” (Burnham), and “a car Jeremy Corbyn drove in the 1960s” (Cooper) are hardly more inspiring.

Blair has written this off as “Alice in Wonderland politics“, but is it any worse than five more years of some dreadful Cheshire Cat grinning down the rabbit hole of focus groups in Middle-England marginals? The Blair-lites have forgotten that politics need not be purely reactive. They’d do well to remember that even Alice herself was no fan of New Labour:

“‘Well! I’ve often seen a cat without a grin,’thought Alice; ‘but a grin without a cat! It’s the most curious thing I ever saw in my life!'”

“But he’s a misogynistic, Holocaust-denying vote rigger!”

Corbyn’s success has brought out the worst in everyone – barring Corbyn himself, that is – and Burnham and Cooper lost my second and third preferences with their eager promotion of “entryism” accusations that never came with any indication of scale.

One Tory voted three times apparently – wake me up if it comes down to these margins, OK? Not least when leaders of labour unions and famously left-wing comedians like Jeremy Hardy (right) are amongst thousands so far denied a vote. A friend who has yet to receive her ballot wrote to me today: “the first time I show any interest [in politics] and now they don’t want me?!” It’s a sorry state of affairs.

The Oscar for worst political actor in a supporting role has to go the media, however. The almost libellous misrepresentation of Corbyn’s statements in the right-wing media was and is to be expected, but more shocking has been the vicious response ofThe Guardian and Channel 4 News.

In the latter case, Krishnan Guru-Murthy and Cathy Newman performed pitiful pit-bull interviews that had Corbyn sympathising with everyone from Hamas to Holocaust deniers. Disregarding his well-documented anti-racism and social-justice work, they instead homed in on tenuous links to people who had a lot to gain from amplifying past interactions, further offering the Jewish Chronicle an entirely uncritical platform to promote its accusations despite its blindingly obvious interest in keeping a vocal supporter of Palestine out of the public eye.

Newman even harried Corbyn into describing a previous encounter with a Holocaust denier who was not at that time a Holocaust denier as a “misjudgement”: past future crime at its worst. In both cases Corbyn’s visible anger and heartfelt grievance were then presented as a dangerous latent volatility – and as news, of course. This kind of interviewing, as Newsnight’s Evan Davis recently noted, involves “mak[ing] people say something … in order to then blow it up into something which isn’t really what they meant. I don’t think that’s a public service.”

But the real killer was the uproar around Corbyn’s proposals to tackle street harassment. Rarely have I been so struck by the real-world value of politics as when this 66-year-old man raised possible solutions to such an insidious problem, inflicted primarily on young women and usually invisible to men.

The reaction? Fixation on one aspect – women-only carriages – as if it were to be imposed by decree rather than potentially piloted only after “consult[ing] with women and open[ing] it up to hear their views on whether [it] would be welcome”. Corbyn’s rivals hummed it, the media sang it. A dispiriting denouement to an outbreak of genuinely worthwhile politics.

But nothing.

So why couldn’t I stop myself from voting for Jeremy Corbyn? Both what he’s done and what’s been done to him have drawn attention to much of what’s wrong with politics in this country today. But rather than join those he supposedly can’t beat, he’s decided to use principled ideas to confront them head on. So far you wouldn’t bet against him…

Image attributions:

1) Labour leadership election voting screenshot (votebyinternet.com), captured and modified by Asa Cusack

2) “Jeremy Corbyn comes to the stage just as the end of the march arrives, two hours after the front arrived” by Beth Granter (CC licence)

3) “Tony Blair – World Economic Forum Annual Meeting Davos 2007” by World Economic Forum (CC licence)

4) “Cheshire Cat” by John Tenniel, public domain from Wikimedia Commons